click to see all artwork at large size

In the taverns along the Anderlay Road you can find some of the

best beer in the East, brewed right there in the cellars under the house. It’s

stronger than wine, and a lot easier to drink then the rum and brandy brought

down by the keg from the northern ports, so it’s easy – too easy! – to lose

your wits while the fire crackles and the minstrels play bawdy songs that come

in with the kegs of spirits.

As evening wears on the minstrels

retire to wet their throats and the storytellers start to mingle. For the price

of a soft bed and breakfast in the morning, they’ll spin you the most amazing

tales, and the best of them are said to be true.

Now, I don’t know how many

travelers would believe the stories to be true, but the Anderlay Road is rich

with legends, and legends have to start somewhere, with some fragment of truth.

Who knows?

Twice a year, I travel the great

road from Dulhanna in the far west to Megadir in the east. I’m Bartali – Raston

Bartali, dealer in spices and rugs, rare wines and even rarer jewels, manager

of fair courtesans, trader in ancient maps to lost cities and new navigator’s

charts drawn from the finest observations of the heavens.

Twice a year, business takes me

from Dulhanna to Megadir and back, while my two wives and five daughters enjoy

the cool of spring and fall at home; and in my travels, I’ve heard every tale

the storytellers know, from one end of the Anderlay Road to the other. Some,

I’ve heard many times, because I have my favorites and will gladly pay a gifted

storyteller to weave it again for me.

One of these is the Legend of

Chino Vollias … and of all the stories told on the great road, this is the one

I wish most were true.

Three hundred years ago, Chino Vollias

was born in the village of Lydris, on the craggy coast of Anderlay, where the

great chalk cliffs are being eaten away by the hungry sea. His mother ran

fishing boats and his father was a mercenary soldier in the service of Duke

Ohmar the Elder; so what was more natural than that young Chino would grow up

as a sailor and swordsman who feared neither the ocean storm nor the steel of

the barbarians who snapped around the heels of the Dukedom.

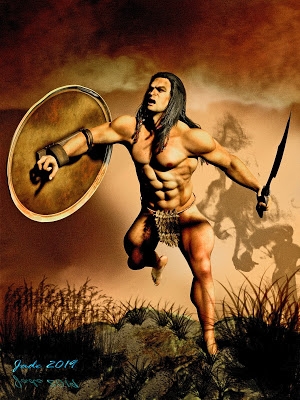

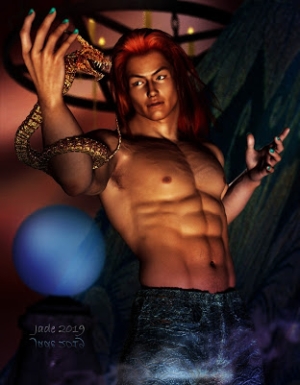

By the time he was twenty-five,

Chino was known as a great athlete, an adventurer, a lover, as unbeatable in a

brawl as in a drinking contest. He had made several fortunes in battle and lost

them to the cards or to capricious lovers, but Chino was untroubled. He was the

best swordhand in all of Anderlay, and one of the best sailors. Another fortune

would always be coming his way before long.

After one grand adventure, he

held onto his wealth for long enough to buy a trading ship, which he sailed to

the port of Lydris, where the vessel was re-rigged, repanted and renamed as the

Carmelita – named after his one great

love, the only woman he could not have.

Carmelita was the wife of Duke

Ohmar; the third, youngest wife, young enough to be Ohmar’s daughter. She came

from Harrandal, across the mountains in the east when she was seveneen years

old to fulfil the contract of a marriage arranged by her father. In return,

Duke Ohmar agreed to furnigh a whole regiment for the defense of Harrandal,

which was much poorer than Anderlay, and ill fitted to defend itself against

the brigands and pirates who rampaged along its shores in those days.

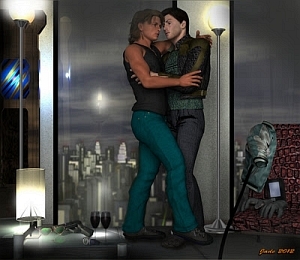

So Carmelita was honor bound to

stand by the contract and remain faithful to the Duke of aAnderlay, for the

sake of her father and her homeland – though she gave her heart to Chino in the

road out of Harrandal, long before the wedding.

It was Chino who commanded the cohort

of cavalry which fetched her west to Castle Mauvais, the ancestral home of

Ohmar’s family. Handsome young Chino and the beautiful Camelita spent two weeks

on the high road, and love bloomed like a wild rose; but it was a tragic love

that left Chino bruised-hearted and, mayhap, a little wild. Four days out from

the Aderlay border, he almost gave his life to protect the party in a despeate

fight against brigands, and Carmelita bound his wounds with strips of the silk

she was bringing with her, for her wedding gown…

Two months later, healed and

strong, he wore the ducal livery and stood at attention in the great temple of

Ghiris, when Ohmar exchanged vows with Carmelita. Chino swore never to love

again, and I think he meant every word, for indeed he never wed, nor settled

with any woman. He had as many mad flirtations with lovesome male courtesans

from Shehend and Elyssan as with the magnificent women who plied the mercenary

trade alongside him, but he gave his heart to none.

And all this, before Chino Vollias

was twenty-three years old! So, little wonder that he named his trading ship Carmelita, and followed every tale of

treasure to be found, glory to be won. Over and over, he sailed back to his

home port of Lydris with full holds and a hundred new stories for the minstrels

and storytellers, who loved him … and they’re still telling those same stories

today –

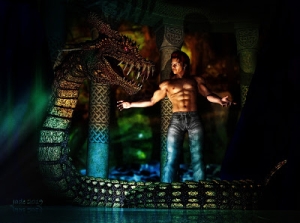

How he fought the Iron Trolls of

Gnothica and won the freedom of the fair Tressida; how he cut the head off the

Black Gryphon to liberate the city of Selendria; how he found the ancient

necropolis of Eldrev and fetched the Carmelita

back to port heavy in the water under the weight of treasure that had been

buried by greedy, superstitious god-kings of old.

And they tell of his last

adventure – which is my favorite tale, heard so often that I can recite it word

for word. The storytellers call it ‘The Gates of Petheris,’ and it begins as

they all do, with the Carmelita tied

up at the wharf in Lydris, the crew a little inebriated at an old sailors’

tavern called The Silver Sword, and Chino himself tangled in the limbs of some

lovely young thing who had taken his fancy.

In comes a man with a broken nose

and two gold teeth. “Where will I be finding Chino Vollias?” he asks.

“What would you be wanting him

for?” asks Toby, the landlord of the Sword, whose back was bent with the ill of

the bones, while his eyes and mind were as sharp as those of a general on a

battlefield.

“I want him to hire him, his ship

and his crew, for a voyage up the coast,:” says the man with the nose and the

teeth. “Then I want to retain him and his crew for their expertise in the

desert. I have a map that shows the way to Zuralia, but I can’t get there

alone!”

The mere whisper of the magical

name of Zuralia makes heads turn and ears prick. Everyone knows the name of the

city – and its fate. It was a great trading city, long ago, before the Borisk

came down out of a sandstorm and settled there. You get a Borisk in your area,

you might as well pack your bags and head out, and warn your neighbors to run

while they can.

No one in Anderlay has ever seen

a Borask … at least, no one has seen one and returned to tell of it. But legend

has it that the Borask is a great serpent, half dragon, half cobra, with red

eyes and the breath of Hell, and a dark magic that no alchemy under heaven can

undo. If a man feels the heat of its rank breath upon his skin –

Well, you know of the goose that

lays the golden eggs. You know of the Gorgon whose gaze will turn a man to

stone. Of King Midas, whose touch turned anything to gold, and the vengeful

gods of the desert people, who turn to salt all those who disobey their

commands.

The breath of the Borisk turns

anything living that it touches into silvergold, that beautiful argentiferous

gold that’s worth more than the all jewels on the hands of the concubines in

the ducal harem.

And legend swore that the people

of Zuralia chose to stand and fight.

So there would be hundreds,

perhaps even thousands of them who stood there like fools and defied the Borisk…

Hundreds, even thousands, of

great lumps of precious argentiferous gold that once used to be the flesh and

bones of idiots. Enough to make a whole kingdom wealthy past the dreams of

avarice. No wonder Toby, the landlord of The Silver Sword, ran right upstairs

and hammered on the door of the chamber where Chino was tangled with some

amorous embrace.

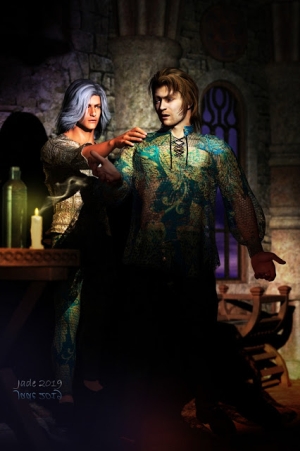

The map uncurled across the table

in the light of six fat candles. It was painted in rare metallic inks on the

polished inside of a piece of leather that had been stretched thin, cured and

bleached to the color of old ivory. It was so old, even the metals in which it

was painted had begun to fade, and Chino knew at a glance, it as real. He had

seen so many of these, he knew a fake at once, and this one was genuine.

But one thing more interested

him. He had heard the accent of the man with the nose and the teeth. He knew

that accent so well, for Carmelita spoke with it, too.

“You’re from Harrandal?” he

asked.

“I am.” The stranger’s name was

Eldrigo.

“And you’re hunting for the treasures

of Zuralia for your own sake?” Chino asked shrewdly.

But Eldrigo was a decent man, and

told him the whole story. To be sure, he would take his fair share of the

riches brought back from Zuralia, but the rest would be spent for the defense

of Harrandal. It would buy the kingdom which was Carmelita’s home a whole

legion of mercenaries.

And then, Chino thought,

Carmelita could ask – even demand – to

be released from her marriage contract, since Harrandal no longer needed the

services of Anderlay. She would be a free woman, and Chino Vollias would be at

liberty to make her another offer.

So he was quick to gather the

crew and tell them to prepare the vessel for another voyage. She would sail

west along the coast which paralleled the Anderlay Road; she would sail for six

days and then the lookouts would be watching for a cove marked by two great

cliffs of blue stone, one of which was shaped like the head of a gryphon.

Hammers rang and voices called

between the ship and the quay, long into the night, while Chino sprawled in his

cabin with a goblet of rich wine in one hand, and in the other, the little

cameo painting of Carmelita that had been commissioned by Duke Ohmar, and was

stolen for Chino by the lady’s handmaiden. And Chino brooded over it, thinking

long and darkly of all that might be.

Two days later, when mist lay like

silver gauze on the harbor waters, the Carmelita

slipped silently away from Lydris. As she left behind the headlands, the wind

caught her great ivory sails and she turned west before a good sailing breeze.

She made good time, racing into

waters that grew stranger and more dangerous with every hour, until all the

gentle, generous ports of Anderlay were left astern and ahead were seas filled

with mystery and treachery. Now, the crew put on their armor, stood lookouts at

every hour of day and night, and kept their swords close. Chino dozed fitfully,

reluctant to sleep while the ship slid on into peril, but in fact the Carmelita remained unchallenged when she

cut sail and slipped in under the great cliffs Eldrigo had described.

Dawn light was pink and gold on

the blue stone walls, and the shadows around the shape of the gryphon made the

monster appear to watch the ship as she sailed into the still, calm waters of

the bay. There, she dropped anchor.

The whole day was ahead of them,

and Chino saw no reason to delay. Eldrigo was keen to be moving, and as for

Chino – he could almost feel Carmelita’s hand in his. He had kissed her once,

and he thought he could still taste her lips, like berries and wine. The kiss

was surreptitious and illicit, stolen in a single moment when her serving women

and his lieutenants had stepped out of the tent. It burned through his whole

body, and thee years later Chino still felt as if it were branded into his

soul.

Before the ship left Lydris, he had

sent a message to Carmelita’s handmaiden, Thora, and he knew he could trust

Thora to set it into no other hand but Carmelita’s. ‘Hold and hope, my dear,’ he had written to Carmelita. ‘We will be back before the winter, and with

the slenderest thread of luck, Harrandal will be well defended and you will be

free. Hold this in your heart, and wait.’

And he signed the message with a

drop of blood drawn from his wrist. The small scar glistened in the sun as the

rowboat made its way from the trading ship to the little beach … and the vast

desert opened up right behind that beach. Sailors called this the Coast of

Skeletons, and sure enough, Chino’s crew began to see the bleached bones of

men, camels and mules before they had gone five miles inland of the beach.

Five men had gone ashore with him

and Eldrigo, and the party of seven carried water and food for four days –

long, hard, thirsty days. Those who know the Coast of Skeletons will tell you,

there are no wells, no soaks, no creeks, save at the depths of winter, and those

creeks run dry before spring.

The city of Zuralia was built a

thousand years before, when the rivers flowed through different channels, when

the rains came from the south, not from the east, and the deserts were not so

cruel. These lands were never kind, but in the great days of Zuralia they were

much more forgiving … the days before the Borisk came. The engineers who built Zuralia

sank great cisterns into the rock beneath the city, vast granite tanks that filled

with the winter rain, and even in high summer they remained full, clear and

cold.

A few paths wound inland, from

salt pan to dune to wadi. Goats could make a living there, eating thorn bushes

and lapping the dew that settled every day at dawn, when the fine sea mist

rolled in and dropped a thin veil of moisture on stone, leaf and thorn. Chino’s

party followed the goat trails while the daylight hours grew hot enough to boil

a man’s brains inside his skull.

They made camp on the edge of a

salt pan under indigo skies where the stars blazed, and the wind stirred

fretfully in the thorn bushes, whispering with the thin voices of fools who had

died on these trails. The men clustered together, hugging the fire and longing

for dawn, though a thin wedge of daylight would fetch back the heat.

But two days from the coast, they

were still looking for the ruins of Zuralia, and had begun to give up hope. If

they did not find the ruins very soon – those cisterns, full of cold, clear,

sweet water – they must turn back for the cove, with enough water left in the

skins to get them there.

And then Chino and Eldrigo saw something. It lay half-buried in the

sand, and it shone in the sun. They stumbled forward and began to dig, and they

soon had it out. The crew gathered around, still only half believing, but their

eyes did not deceive. It was the skull of a man, yet it wasn’t made of bone. It

seemed to have been cast in argentiferous gold.

“Zuralia has to be close,”

Eldrigo said eagerly.

“According to that map, we should

be right on top of it,” the swarthy little mariner, Rashid, added.

“Not more than an hour or two

from here,” Chino agreed. “But there’s one thing we never talked about.” He

looked at each of his men in turn. “The Borisk.”

“You mean … it might still be

there?” Rashid whispered.

“Damn.” Eldrigo’s face whitened.

“After all these years? Surely not!”

Lesser men would have turned

back, but Chino’s crew had followed him to Hell before this, and lived to tell

the tale. They were not about to turn back now. Each carried a number of sacks,

to carry as much as they were able away from the ruined city, and they were

shaking them out, getting them ready, while Chino thrust this first lump of

gold into such a sack and slung it over his shoulder.

The map sent them around the edge

of a saltpan that shone whiter than ivory in the sun, and as they crested a low

rise on the southwest side of it, Eldrigo began to shout. Shading his eyes with

both hands, he had seen the tumble of ruins in a place where the sands were

swept level by the wind and the glare was blinding.

It was much further away than

they had thought, and the sun was down before they stumbled into the ruins. In

the twilight, they searched frantically – and their desire was not gold, but

water. Rashid found the way down, a stone stepway winding into the basements

under the city, and Chino held his breath, praying…

They were in luck. The ceilings

had held up for enough of the way, permitting a man to walk through passages

where the dust was an inch thick. No human feet had trodden there in centuries.

Like goats and camels, they could literally smell the water, and followed their

instincts to a great bell-shaped chamber where the floor glistened in the light

of torches –

No, it rippled, for it was not ground, but water. Lakes of water, gathered there and untapped since the

population of Zuralia either fled or was turned to gold. The crew of the Carmelia stripped naked and dove in.

They swam, drank, bathed, in the vast lake of dew-sweet water. The goatskins

were filled again as they rested on the edge of the pool and, shivering

pleasantly with the first cold he had felt in so long, Chino climbed back up to

the ruins to get warm, eat, watch the stars, make plans.

Tomorrow, he thought, they would

begin to hunt for the silvergold handiwork of the Borisk. He set a lamp, sorted

the contents of his pack, and as moths began to flutter around the light, began

to eat a meagre meal of jerky and dried fruit.

To Chino’s mind, it stood to

reason that the gold would be buried, because the big winds from the deep

desert would have covered this city with sand and then uncovered it, time and

time again, since the Borisk laid waste to Zuralia. There would be gold everywhere,

in the places where people too stupid to flee had made their last stand against

the monster. He only needed to find the ramparts, the fortifications, and

enough gold would surely be underfoot there to free Harrandal – and Carmelita

with it.

He was tired and his mind

drifted, not quite asleep. He saw Carmelita’s lovely face so clearly, heard her

voice. She reached out a hand to him, so near, he thought he could feel the

warmth of her skin as she moved against him. Her nearness had begun to stir him

when he actually heard what she was saying.

Her voice was thin, ethereal as

the dawn mist. “Chino,” she said, “Chino, listen to me – you must listen to

me!”

“I am listening,” he said, though

he was reaching for the phantasm her, wanting to bury his face in the soft

mounds of her breasts, breathe in the scent of her hair, feel the strength of

her arms as they wrapped around him.

“Chino!” She seemed almost to

hiss into his ear. “Listen to me!”

A last the urgency of her voice

reached him, and he began to concentrate. “This isn’t a dream, is it?”

“No! It’s not a dream – it’s me,”

Carmelita promised. “I got your message, when you shipped out of Lydris. I know

where you’ve gone – in fact, I know where you are! You’re at the ruins, aren’t

you? The ruins of Zuralia.”

“Yes.” He was astonished. “How do

you know this?”

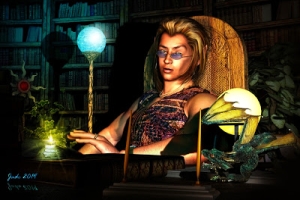

“Because I was so afraid for you,

I went to the witch, Magdala … I paid her a prince’s ransom to work this magic

for me.” Carmelia paused, and as Chino listened harder her voice gained

substance. “Look around,” she said. “Do you see a black bird, a crow?”

His eyes opened to slits, he gazed

around the ruins, and sure enough he saw it. “I do,” he said. “How could you

possibly know that?”

“The bird is the familiar of

Magdala,” Carmelita told him. “It’s followed you. It rode in the rigging of

your ship, but you didn’t see it … Magdala sees through its eyes, and she’s

worked this magic to let me speak to you.”

“Can she work more magic, let me

see you?” Chino wondered, for he would have loved to see Carmelita, whom he had

only seen fleetingly, from a distance, and at state occasions, since she was

wed.

“Would that it were possible,”

she said sadly, “but – listen, my love! Listen well, and do as I bid.”

He listened, and was horrified.

He must gather his crew, she told him, and they must be out of the ruins of Zuralia

by dawn. “But, why?” Chino demanded. “We found the ruins, and we’ve already

found one skull – pure silvergold, Carmelita, just as the legends swore. Twenty

or thirty of these will be the price of a legion for your homeland, and freedom

from you, and there’ll be hundreds here!”

“What do I care about my freedom,

if you’re dead?” Carmelita cried. “Don’t you know, Chino? Has Eldrigo not told

you? Or, perhaps he doesn’t know … the Borisk is in the city! Magdala knows this. It’s there, even now … it

hibernates in a chamber below the ruins. It sleeps until it’s disturbed, and

just being there, walking its passages, breathing its air, you’ll disturb it.

At dawn, it’ll rise with the light of the new sun, and you’ll join the

silvergold bones in the sand. Run, Chino – get your people together, and run!”

“And what of your freedom?” Chino

asked wistfully even as he began to stuff his things back into his pack.

“My freedom, against your life?”

Carmelita said in sad tones. “No, Chino. If only one of us can be free, I want

it to be you. Be quick, now!”

Her voice was fading out even as

she spoke, and Chino struggled to reach her. But she was gone, and in a fine

fury he called softly for his friends, and for Eldrigo. He pinned Eldrigo with

a gimlet-eyed glare, demanding to know why he had not been told the Borisk hibernated

under the ruins.

But he knew by the way Eldrigo’s

face blanched, the man had known none of this. “Maybe the witch is wrong about

this,” the man from Harrandal began.

But Chino knew the truth of it.

He knew Magdala by reputation – had known her all his life. She might have

looked like a young woman, but she was older the foundation stones of the ducal

castle; her powers were vast, and she was never wrong.

He knew his crew had two chances

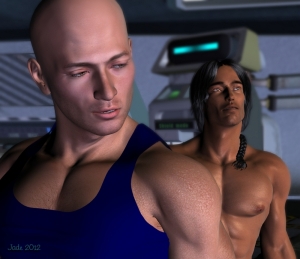

– and running away was by far the safer of them. However, there was another,

and he put it to his men, rightly judging that it should be up to them to

choose their own fate.

They could run before dawn, and

they would make it back to the ship with one piece of silvergold, enough to pay

for three voyages like this one, so they would not go home empty handed. Or

they could draw swords, head down into the catacombs beneath these ruins … they

could seek the lair where the Borisk hibernated, and slay it like a bear in its

den. Slaughter the ,monster before it could wake, and they would be free to

claim the treasure of Zuralia.

His crew were mercenaries,

seaman, adventurers, afraid of little so long as they had a fighting chance,

and he knew what they would choose. Swords and lances gleamed in the lamplight;

whetstones slithered, sharpening blades; hair was braided as the men made ready

to hunt.

A second time, Chino heard the

voice of his beloved, and he closed his eyes to concentrate on it. “Don’t,”

Carmelita begged. “Please gods, Chino, don’t do this. Magdala sees with the

eyes of her familiar – she knows what

you’re doing. Please, get out and run before it’s too late.”

“It’s too late already,” he told

her softly. “The men have chosen their own destiny, as is the right of all free

men. They’re ready to hunt.”

“Then, you be ready to flee,” she insisted. “Don’t let the creature’s

breath touch you! Be fleet-footed, don’t stand and fight, for you can’t. Run

into the rising sun, my love – the creature is blinded by the brilliance of its

light, when the sky is clearest in the early morning. Look for the gates.”

“Gates?” he puzzled, wondering if

he had heard correctly.

“The Gates of Petheris,”

Carmelita said urgently. “Look for them! Promise me, Chino – promise me you’ll

look for them. They’ll seem to you like a mirage, but you must make for them,

with the last breath in your lungs and strength in your body. Magdala has

wrought a great magic for me. I’ve paid her with the emeralds the duke gave me

when I was nineteen. Magdala will be rich, and this will surely be her last

magic, and her greatest.”

“A mirage,” Chino repeated.

“Yet, not a mirage.” Carmelita’s voice was dwindling again, and he

listened harder. “They are the Gates of Petheris, and you’ll be safe…”

Then her voice was gone, and

Chino’s heart hammered against his ribs. He had heard this legend, he was sure,

but not in many years. It was very old – the stories of Petheris were told by

his mother’s father, who had been in his dotage, almost at the end of a long

life, and dimly recalling what had been told to him in his boyhood by his own

grandfather.

Petheris … was it a place, or a

person? Chino did not know for sure, but he remembered enough to know that

beyond those gates was another land, fabled, splendid, safe. A land from which

no one had yet returned, but the legend swore it was possible to come back, if one were determined enough, and strong

enough.

This was the last, greatest magic

of the most powerful witch at the duke’s court – to open the Gates of Petheris

for him, if only he could run hard and fast enough to stay out of the breath of

the Borisk? Chino swallowed his heart, and faithfully recounted what he had

been told to his crew.

Wide eyed, they heard him out,

and he hoped they would suffer a change of heart and decide to quit Zuralia

while the hours of night were still young. But no, as one, the whole company

turned down the cracked marble steps into the basements and cellars under the

ruins, intent on hunting.

The city seemed to stretch for

miles underground, and many times Chino was sure he was lost. Then a gap would open

up in the ceiling and he could look out, see the stars. He held onto a tenuous

grasp of his bearings while the crew searched from hall to hall, down passages

thick with the dust of eons, until at last Eldrigo’s sharp ears picked up a

sound, and he held up a hand to stop them.

They listened, ears straining in

the absolute quiet of the cellars … and Chino heard it too.

A rasping sound that might have

been breathing, and a slithering that could have been the coils of a great

serpent shifting and moving in its sleep. They had it! Now, swords slid

silently out of scabbards, and Chino led the way on soundless feet, following

the soft shush of the creature’s breath.

They rounded a corner and came

into a vast hall where the roof was partly open to the sky, and vines and

creepers had intruded, sinking roots into the cisterns down below. And here,

Chino knew at once, they were wrong. The sounds they had heard were not the

creature shifting in the depths of its slumber.

Carmelita and Magdala were right

– the mere presence of humans in the city had disturbed it. The Borisk was awake,

rearing up on its coils, with massive fangs bared as it turned toward them, and

it gave a sibilant roar as its glistening forked tongue darted toward them.

Rashid – always impulsive, seldom

wise – was the first to try his luck. He flung a javelin, and another. The

first was turned aside by a shrug of the creature’s armoured hood. The second

struck it square in the coils, where its breast might have been, but bounced right

off. Its armor was too thick to be damaged by a spear, and Chino doubted that a

sword would much hurt it. Rashid was caught just as he turned away and tried to

withdraw, and with wide eyes his fellows watched him turn to silvergold.

The next to try – and the second

to pay the price for rashness – was Eldrigo, who rushed forward with an axe in

either hand, trying to dodge the Borisk’s head, stay out of the draft of its

breath. He hacked at its body, at the

places where the armor plates joined, and it might have been vulnerable.

Watching closely, Chino saw that Eldrigo

never even drew blood. The incredible creature seemed merely infuriated by the

blows and, faster than Eldrigo could hope to move with human limbs, it spun,

twisted, breathed long and hard on him.

It seemed a chill rushed through

Chino’s whole body as he watched Eldrigo of Harrandal freeze in place, solidify

right down to the tips of his long hair, as had Rashid, and take on the luster of

pure silvergold. But the Borisk was not done yet, and its long neck darted out like

a snake, faster than Mahmed, the young steersman of the Carmelita, could get out of its way. It had him even before Eldrigo

had finished changing, and Mahmed was gone.

Three of them – half the party –

were lost in as many moments, and Chino knew by now, victory today would be

measured in sheer survival.

He was shouting this at his men

while the thin, breeze-like murmur of Carmelita’s voice whispered into his ears,

“Run! Chino, for the love of all the

gods, run!”

It might have been the first time

in his life that Chino Vollias or any of his men had turned their backs on an

enemy and run, but they had the good sense to do as the lady bade they. Chino

was yelling for the others to follow, but did not look back as he hurled

himself up through the rent where the roof had caved in, and was suddenly in

the ruins. He heard them scrambling, right on his heels, and willed them to

speed.

Where had the night gone? They

had all lost track of time, and were astonished to see dawn on the horizon as

they rushed through the tumbledown columns and walls of the ancient city.

What had Carmelita said? Chino

must run into the rising sun, for the Borisk was blind in its brilliance, and

he must not stop until he had seen what looked like a mirage. He shouted this

to his fellows, exhorting them just to follow. They had no water, they were

racing out into the desert; return to the ruins was certain death and they were

too far from the cove to make it back to the ship. They had one chance – the

Gates of Petheris, which would swim before them like a mirage, mocking them.

Like an athlete, Chino ran. He

dropped his weapons, for they were useless. He was close to naked, as he had

bathed, and like the athletes of old, he hurdled the ruins and sped out into

the desert, into the dazzle of the dawn sun.

He heard the sounds of his

crewmen behind him – he was sure he heard one of them scream and surrender, but

the others hung on, still. If they could not make enough speed to stay one step

ahead of the breath of the Borisk, there was nothing Chino could do to help

them. Anyone who turned back would only give his life in the futile attempt,

which no man among the company would ever have permitted, much less asked.

Every man juggled his fate between his own hands, and the prize, the ultimate

victory, now was survival.

The crow flew with them, cawing

rudely as they fled, chasing the sun into sands that were soon baking with

heat. Chino ran until his legs trembled, his lungs ached and his throat rasped.

His head swam with exhaustion as the sun climbed, but he did not look back, and

as the heat haze began to shimmer over the sands, he was hunting for the

mirage.

He was slowing down, he knew. The

Borisk could be back there – he could not know for sure without stopping,

turning to see, and if the creature were there, trying to glimpse it would be

his death warrant. Instead, he forced himself on, fleeing into the sun.

Exhaustion dogged every step, his

body begged for rest, his lungs were spasming and he began to stumble. He went

down in the sand, dragged himself back up and plunged on, slitted eyes raking

the distance, hoping, praying, that the last, greatest magic of the witch Magdala

would not be wasted.

And then, when he was sure he

could not walk another step, much less run, he saw it. The gates were misty, as

if made of glass that shimmered and wavered in the heat haze. The Gates of Petheris

stood open, and he dove toward them, though the mirage mocked him with

transparency, fading in and out as if it would vanish utterly before he reached

it.

He was not even breathing when he

and two of his men, the last survivors of the Borisk, tumbled through the gates,

and they swung closed one instant before they faded back into nothingness, as

mirages do…

And there, the storytellers

pause. The end of the tale was fetched back by a camel driver who had chased

his animals into the desert, and saw the magnificent athlete, spent and at the

end of his endurance, vanish into the mirage along with two companions who had

doggedly followed his lead.

The rest was recounted by Magdala

herself, for she had seen and heard it through the eyes and ears of her

familiar. The crow flew back to the ship, which waited two more weeks for Chino’s

party to return. But no one ever walked out of the desert, and at last the Carmelita turned back for her home port

of Lydris, bearing sad news.

But Magdala, grown rich on the

emeralds she had received in exchange for her magic, promised Carmelita this

was not the end at all. The magic had stripped her powers away. Everything she

possessed, she had given to open the Gates of Petheris and to let Carmelita

speak to Chino – the price of his life. She would make no more magic, but she had

one more promise for the third, youngest wife of the aging Duke Ohmar; and she

made the promise as a mortal whose gifts were wholly spent.

Petheris is a land beyond, she

told Carmelita. The gates are hard to find and harder to enter, and people who

step through don’t return – not because they can’t, but because they have no

desire to. Once they have discovered the shining land of demiurges and demigods,

of light and music, wonder and magic, the world of mortal humans had nothing to

offer. Or, Magdala added shrewdly, nothing much.

If Chino Vollias returned from

Petheris, it was surely love that brought him back; but did he return?

No one knows for certain, but

there are stories … there are always

stories. It’s a matter of history that within a year of the ill-fated

expedition to Zuralia, prospectors struck gold in the mountains in the south of

Carmelita’s homeland, and Harrandal was suddenly as wealthy as Anderlay. The

royal household recruited a powerful legion which was trained by the best

officers from Duke Ohmar’s regiments. Carmelita was free to ask for her

marriage contract to be dissolved –

And she did. Everyone thought she

would go home at once, but instead she and the handmaiden, Thora, and Magdala,

the witch whose powers were gone, made their way to the harbor town of Lydris,

where they took a house overlooking the harbor, and waited.

How long they waited, no one

knows; but soon enough the records of the town show the house at the head of Rigger’s

Lane to be held by two women, not

three. In the years that followed, Thora’s name appears in the register as the

mother of several sons born to a handsome sea trader, while Magdala was

notorious for gambling on horses – and winning, as if she still had enough

second sight left to unerringly pick winners. She became unspeakably rich, and

even though she began to grow older, as mortals must, young men adored her as

if they were enchanted; and of course, there were rumors.

Of Carmelita, history soon lost

all trace, just as it records nothing more of Chino Vollias. The two fade away,

leaving one to wonder, and hope.

There, the storytellers wind down

and look for beer to quench the thirst of a long tale, well told. They’re

always given the best, for the Legend of Chino Vollias is a favorite; and as

for the ending … everyone knows what he wants to believe.

**********************

Happy Post 700!

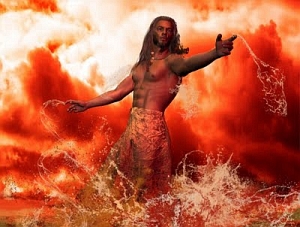

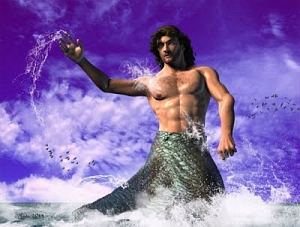

I promised something special -- and special things take a bit longer, so you'll forgive me for the delay. These pieces took lot of work ... they're highly finished and intensively painted, but they're soooo beautiful, too, and well worth the wait.

Actually, it's been fantastic for me to do this, because it gave me two "firsts." This is the first actual, finished piece I've done and uploaded. And also, this is the first project where I got to use my new pen/tablet. Yoo might know I have a birthday coming up. Well ... I shopped around and found the Wacom Bamboo pen/tablet of my dreams, told Dave. Next thing you know, a courier is leaning on the doorbell. But it's still seven weeks to my birthday. I couldn't wait that long. Just couldn't. So the Wacom Bamboo with the lovely foot-wide tablet is standing on the desk beside The Mighty Thor, which has been running like a dream since last Boxing Day.

Happy, happy, joy, joy!

Hope you enjoyed this project -- and please do download the art at large size, to see it properly. Have been asked more than once if I'd make some wallpapers, and I will definitely do this. Also, I'm going to add a Writings Page to my gallery site, and I'll be able to do a real, proper presentation of this story, and many more like it, right thee. There's only so much you can do on a blog, right? Especially since everyone who's reading on a smartphone (guilty!) sees a way, way simplified version of the layout. Sure, it's nice to read on the phone ... convenient ... but it's also nice to sometimes visit an actual website and see a gorgeous layout.

Next: the next chapter, or even two, of Abraxas...

Jade, September 16