Chapter Seven

The night’s misadventures seemed to haunt Martin every mile of the way back to the city. His face was shuttered, his eyes often downcast and filled with shadows. He murmured once that the journey seemed much longer than he remembered, and Leon could appreciate that. Remorse was a harsh taskmaster.

A little before noon — when the sky was lowering with incoming weather and the old folk would have been starting to talk about the chance of a shower by evening — they were on the Esketh road, which wound around the long, gentle slopes that climbed up out of the badlands. Ahead of them was green, fertile country following the banks of the River Esku; and there, in a place where the forest had been cut back centuries before to clear space for farming and building, was the city itself.

They called it the ‘Rose of Rasanu,’ since it lay at the heart of the old kingdom, and the name was fitting. It was easy to see why this land was guarded so jealously, and from the look on Martin’s face, Leon knew full well, he was keenly aware of the necessity for the militia, the requirement for young people’s service in it. Martin had no argument to make against the system; only with the part he rightly ought to play in it.

As a flight of waterfowl shot low overhead, on their way to the river, Leon pulled up the horse and slid down to walk for a few miles, stretch his legs and rest the vanner at the same time. On the shoulder of a hill he stopped to look out at the view of Esketh, and gave a low chuckle.

“Damn, where does time go to? It has to be ten years since I saw the city from this exact spot. I’d forgotten how beautiful it is. It’s so … so green.” He glanced sidelong at Martin. “You haven’t traveled far, have you?”

“No. I’ve never had the chance,” Martin admitted. “I thought, one day…” He shrugged, let the idea go by.

“The more you travel,” Leon told him, “the more you’ll realize how precious is your own home. Not many places are so green, so welcoming, as this. Esketh is so different.”

“Different from what?” Martin looked up at him out of wide, blue eyes, eager for anything he could learn of the world beyond.

“So different from the lands where I’ve been soldiering for far too long,” Leon said with a humor so dry, it was arid as the eastern steppes. “Places where the trees burn brown in the sun and you often draw your pay in water, which is the most precious commodity they know. Places were common water can be sold and bartered for gold and jewels, and is smuggled like diamonds.”

“Where?” Martin wondered.

“North and east of here.” Leon gestured over his shoulder. “Far beyond the Anghari roads. My people only roam as far back as Setzele. A dozen miles beyond that, and they’d be in territory belonging to the Venhira, and it would be drawn swords and spilled blood.” He gave Martin a look of dark amusement. “The roads and ranges were decided at least a thousand years ago. So long as the Gypsy clans stay where they belong, there’s peace.”

“At least you know where you belong,” Martin said with a bitterness that was unusual in one so young.

Leon dropped a hand on his shoulder. “You’ll find your place in the world — or make it. You’ll be home in an hour.” He tilted his head at Martin. “Have you worked out what you’ll say to Roald — and how you’ll say it?”

A wind stirred restlessly across the hills. Leon thought he smelt the sea on it, and memories of fishing boats, and cockleshells bobbing in the estuary, rustling fields of reeds and flights of gray swans, flooded his mind as Martin raked the blue-black hair out of his face and said,

“Roald’s been very good to me for a long time. But I told you how he’s been watching me lately, waiting for me to pick up a sword — go soldiering like him.” His brow creased. “Like you.” The dark head shook slowly. “He knows by now, I can’t … won’t. I’m just not a soldier, Leon. Is that so wrong? Is it so bad?”

But Leon only shrugged. “It’s not wrong or bad at all. But for more than a century that anyone recalls — and a lot longer, that they can’t! — the tradition has been militia service to safeguard the city. Esketh depends on not having to hire mercenaries. This is why the city is rich, prosperous. If the city fathers had to pay an army of bastards like me to keep them safe, they could only do it with taxes and tithes. There’d soon be poverty.” He shrugged eloquently. “The occasional lad going against the tradition isn’t a bad thing, but it’s going to make your life … different. Difficult.” He lifted a brow at Martin. “You have to know this.”

“I do know it.” Martin sighed. “I’ve always known it. But … surely I have a choice! There has to be something else, instead of the militia.”

“There’s always a choice,” Leon said thoughtfully. “You just might not like what it is.” He looked Martin up and down with a deep frown. “Do you want me to talk to Roald for you?”

“You’d do that?” Martin seemed to pull his shoulders square. “Damnit, I should talk to Roald myself. I’m trying to take charge of my own life, not pass responsibility to someone else! I made a mess this time, but I can do better.” He raked the wind-tossed hair back out of his eyes and looked northwest, and down, toward Esketh. “I’ll talk to Roald,” he said softly. “You … you talk to the sheriff. All right?”

“All right.” Leon stirred. “Come on, now. You can be home in an hour.”

Even on foot, from here it was not more than an hour’s journey, and it was downhill most of the way. The river curved away in the north, where the estuary smelt of the sea and sounded of birds; a patchwork of fields skirted the city, separating it from the hills, and at last the walls rose, gray, sturdy, ancient, protecting everything Esketh was.

Even on foot, from here it was not more than an hour’s journey, and it was downhill most of the way. The river curved away in the north, where the estuary smelt of the sea and sounded of birds; a patchwork of fields skirted the city, separating it from the hills, and at last the walls rose, gray, sturdy, ancient, protecting everything Esketh was.

The quietest way back into the city was by the old gate, Leon knew, the gate on the east side where the traders and the Gypsies did business, camped, came and went from the pre-dawn light till twilight and curfew. He did not have to ask Martin which way through he preferred; the kid’s head hung, his eyes were downcast, and if he could have slunk into Esketh unseen, he would have done it.

The smells of the city were so familiar, Leon felt that they welcomed him home. The Anghari were still here; he heard the music of his people from the gaudy encampment outside the walls, and the pungent aromas of their food teased his nostrils. Another day, he would have stopped there to see who had come to Esketh this year — his cousins, aunts, uncles, perhaps even a few of his elder siblings.

Today, he cut a line directly for the gate, out of consideration for Martin. And even there, people were looking. Martin probably knew most of them — Leon himself recognized a few faces, and one in particular.

It was a disagreeable character whose ugly face had not improved with the years. Since militia service he had always worked for the sheriff’s office, and if Martin had hoped to get home unnoticed, he was disappointed. He swore softly under his breath and Leon said quietly,

“You on on ahead. I’ll catch you up.”

From the look on the kid’s face, he wished the ground would just open up and swallow him whole, but he was lucky. You had to be alive to be aware of the burden of shame and remorse. This morning, Leon thought as he watched Martin duck his head and hurry away, the kid was wise enough to be counting his blessings.

He had gone, cutting a swift line through the old gate and heading for home without looking back. Leon leaned on the horse’s shoulder, waiting for the sheriff’s man to speak. Gray eyes looked him up and down with something very like contempt, and Leon stifled a chuckle. Once, he might have cared. Not now. Not in years.

“Welcome back to Esketh,” Borgas said gruffly. He was a big man, but most of his bulk was suet rather than muscle and sinew. His voice was hoarse, and Leon remembered how Borgas liked the hookah and the tankard a little too much for his own good health. “You’ve been gone a long time,” the man was growling.

Was it Gypsies in general Borgas did not like, Leon wondered, or was in just Leon himself? He had never been sure, and even now he was less than inclined to spend enough time with the sheriff’s man to find out. “You know where I’ve been,” he said easily. “Soldiering. And now I’m back.” His brows arched at Borgas, challenging him to make something of it.

For several seconds it seemed Borgas would — perhaps questioning Leon’s citizenship. He had the right to do so, but it would have been useless posturing. Leon had served the full term with the Esketh militia; he had the right to live here for life. At last Borgas shrugged and stepped aside.

“You bought in the curfew breaker,” he observed.

“Yes, I did.” Leon caught the vanner’s reins. “Why don’t you run and tell the sheriff that he’s back? And at the same time, tell the sheriff to talk to me about it.”

Borgas’s lips compressed. “Sheriff Heide will be talking to Roald Mendsen this evening.”

“But it’s not Roald’s responsibility,” Leon told him in the same unruffled tone. “It’s mine. Heide’s wasting his time, talking to Roald — but I’ll be at the Mendsen house. Tell him to ask for me.”

With that, he walked on by, making Borgas step further aside to accommodate the horse as he made his way through the old gate and into the quietest part of Esketh. And there, he stopped. Eight years, and nothing had changed, as if nothing ever would. The houses were old, all red shingles, leaded windows, sculpted stone, with high garden walls over which flowering creepers climbed and cascaded.

The place had a smell, a feel, a sound that was unique. In all Leon’s travels, he had not found another place that reached inside and touched some nerve, made him welcome. If any place in the world said ‘home,’ this was it, and Leon indulged himself in a full minute with his eyes closed, letting the town seep in through the pores.

At last, the horse tossed his head and snorted, making Leon chuckle. “You’re hungry,” he guessed. “You want a stable, a rub down, a pail of oats and apples, sweet fresh water, straw right up to your knees … get down and have a roll. Come on, then. I know where we can find all that.”

At this time of year the streets were a little dusty, the trees looked thirsty, but Esketh had plentiful water, from the river and numerous deep wells. After dark, a cart came around and the city watercarriers poured huge leather buckets directly into the roots of the trees lining the wide avenues. The city paid for all this — Esketh was rich. It was wealthy because of the militia, where service was some odd mixture of the voluntary and the mandatory. The kingdom of Rasanu never paid in gold, diamonds and emeralds to hire whole regiments of mercenaries, and the common people reaped the benefits.

But the tradition had a darker side, just as Martin had discovered. If and when a young man found himself unwilling to accept his place in the militia, the city would never recognize him as a grown man, no matter how old he became. He would never have the rights and privileges of an Esketh freeman. He was welcome to live there all his life, but he must observe the curfew, ask permission to marry, and he would never own property or a business of his own. He would labor for someone else, draw a wage, rent a house, and apply for permission to wed, which could be withheld for many reasons, or delayed for years. In all practical terms, the law would treat him as an underage youth, though he was fifty or seventy years old.

If the system was fair or not, Leon did not know. He had never given it much thought, since he had never been caught in the spokes. Without a doubt, Roald would have thought it through when Martin came of age and said no. He would have examined all their options — and he must have come up blank, Leon reasoned, since Martin had tried his luck out on Barran’s Heath.

His feet took him back to the Mendsen house without him needing to tell them the way. He stopped in the shade on the opposite corner, smiling at Roald’s tall, wide gateway with the trees inside and, far beyond, the red-roofed house he had inherited from his parents. The smile widened a moment later as figures moved in the deep shadows at the gate, and he saw Martin and Roald himself.

Roald never seemed to change. He was as pale as Leon was swarthy; he was slender, with a lean, whippy strength Leon remembered from years gone by; and he was as blond as Leon was dark, with ice blue eyes and a face that, feature by feature was not handsome, yet when you viewed them all of a piece, were beautiful. A lovely girl called Imara had taken one look at Roald, and fallen head over heels. They were married three months later, and the first of their four children was born within the next year.

And if Leon had stayed at home in Esketh? Roald could have been just as happy with Leon. He liked men and women equally, and actually he liked children, which Leon did not. From the stories he had told Leon across the years, he loved having kids in the house, whereas Leon had no affinity whatsoever for younglings — not till they reached the age of twelve or fourteen, which was adulthood in the Anghari camp. A few strides beyond the city walls, girls were legally wed at twelve and often became mothers soon after; boys were ‘blooded’ in battle or on the hunting trails at fourteen, and were granted every right and privilege of the free Anghari.

And to the Anghari, the word ‘free’ meant just that. They liked the steppes, the open tundra, the vastness of the mountains; the abhorred walls of any kind, much less doors, and curtains that stopped a man even seeing out. Leon was the exception. He liked green gardens and sparkling fountains; he could read, and liked to. He enjoyed civilized eating, with silverware, off plates, listening to musicians playing delicate, intricate music, rather than swilling beer and eating with his hands in the smoke-heavy air of a tavern, listening to coarse songs and watching dancers of both genders flaunt themselves lewdly.

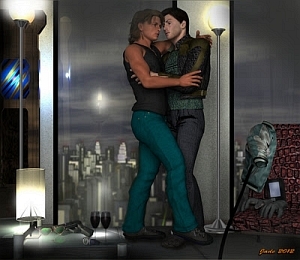

As he crossed the avenue, Roald came to the gate and stopped there, arms crossed, watching as Leon approached. The breeze caught the long, blond hair, and Roald was smiling. “Leon … Leon, you still look fantastic,” he said, echoing the greeting he had made the day before, when he had sent Leon on an errand into the badlands. “I’m so sorry about the trouble — and I’ll make it up to you tonight. You’ll have the best of everything.”

“Don’t worry about it,” Leon said easily as he stepped into the shade, and a stableboy came out to take the horse. The vanner went with him without complaint. He was used to being in the care of cavalry stablehands. He was also used to the ‘the best of everything,’ and if he did not get it, he would let the stableboys know, with glares and snorts and snapping teeth — he never actually bit, but he knew exactly the signals humans understood. Leon gave him a pat as the lads led him away to the stables, and then transferred his attention to Roald. “We were lucky. The gods must have been watching. Martin ran right into Yussan, and I got there before Yussan could make him vanish.”

“Ah.” Roald opened his arms and invited Leon into an embrace. “I see Yussan around the Gypsy camps now and then. He comes in to trade when the Anghari are here, and we share a few words. He wouldn’t have known who he’d caught last night, or he might have let Martin go. Then again, he also might have had a good laugh and upped the asking price, since he’d have known that as a ward of mine, Martin can read and write and already has good manners.” He looked along at the younger man, and sighed.

While they spoke, Martin was standing back in the shadows, reluctant to join them. His head hung, as if he thought he would be punished again, but Leon said softly, “I did as you asked, Roald. The price is paid.”

“You tanned …?” Roald’s brows rose.

“Comprehensively.” Leon shrugged the matter away. “I’ve also already informed that weasel, Borgas, to tell the sheriff to come see me, later.”

“And you know what you’re going to say to him?” Roald wondered shrewdly.

“I think so.” Leon looked his old friend up and down with a fond, lopsided smile. “You look prosperous.”

“I am prosperous,” Roald affirmed. “Come to that, so are you.”

“The account books —?”

“Make satisfying reading.” He stopped and gave Leon an odd, taut look. “Please gods, tell me you’re done.”

“Done with soldiering?” Leon asked.

Roald’s blond head nodded, and he raked the hair out of his eyes.

“That depends on how satisfying the account books are!” Leon managed a creditable chuckle. “You want me to stay this time?”

“And last time, and the time before,” Roald said with self-mocking honesty. “But you weren’t ready.”

“No, I wasn’t,” Len agreed, “and besides … it can’t be like it was between us, can it? Imara knows what we were to each other, when we were Martin’s age, but I doubt very much that she’d approve of the nasty big mercenary seducing her husband under her own roof!”

At this, Roald laughed out loud. “Well, you never know with Imara, but — I take your point.” He leaned closer and dropped his voice. “Martin seems to have taken quite a shine to you.”

It was Leon’s turn to chuckle. “He said so?”

“Not in so many words. But can’t take his eyes off you, and it’s Leon said this, and Leon did that, and Leon thinks the other.” He gave Leon a curious look. “You tanned him last night?”

“Comprehensively,” Leon assured him. “And then held him while he wept, and kissed him,” he added thoughtfully.

“Ah. I thought so.” Roald looked along at Martin, who was still standing in the shadows. “He told me why he went out there.Plain speaking, nothing hidden, nothing held back, and I appreciated the candor. He did all the wrong things for all the right reasons.”

“That’s an apt way of putting it.” Leon stirred. “Can we talk about this later? There’s a lot to be decided, Roald, and I’m sweaty, dusty, smelling of leather and horse. I want to bathe, and if you can lend me something civilized to wear…”

“Of course. I promised, nothing but the best.” Roald stepped back. “Sweaty and dusty you may be, but you still look great. Martin thinks so. You know the way — down to the house, the big bathroom on the east side. Tell the servants to draw water for you, put out the best towels, and I’ll raid my closet, see if I can find something to fit you and do you justice.” He looked Leon up and down again, with a shrewd eye this time. “I know what’ll look good on you, you Gypsy.”

He was turning back toward the house as he spoke, and Leon followed, though he took a moment to look into the shadows, searching Martin’s face. “I told Borgas the weasel to tell the sheriff to ask for me, not you. We can expect in later in the day.”

“Then, I’ll make myself scarce until I see the sheriff walking away,” Roald decided. “Don’t worry about running into Imara and the brood. Imara is at market, shopping for dinner, and the children are in classes.”

Leon was surprised. “Even the youngest?

Again, Roald laughed. “It’s been four years since we talked about the family! We never seem to get around to it, when we meet in this port or that frontier town. We had better things to do, am I right?” he wiped the smile off his face and said ruefully, “My youngest is Rockne. He’s four, Leon. He can already read simple words, and I think he’s going to be an artist. That is, if the drawings we have to scrub off the walls of the house every few days are anything to go by! Come on, come and bathe. I’ll fetch wine, and you can tell me the stories of this last twelve months, while you luxuriate in hot water and soap.”

“You persuaded me,” Leon said with wry humor. He fell into step with Roald, headed down between the marble pillars and onto the terracotta path to the house, but Martin did not follow. Leon glanced back again, but the younger man’s face was wreathed in the shadows of the hot afternoon, its expression impossible to read.

With a sigh, Leon set the matter aside and listened to Roald, who was talking about the family boats, trade — and those accounting books which detailed Leon’s future and told his fortune more adroitly than a fortune teller in the Anghari camp.

NOTE: The Abraxas Contents List is in the left-side column -- quick links to each chapter

NOTE: The Abraxas Contents List is in the left-side column -- quick links to each chapter

**************************

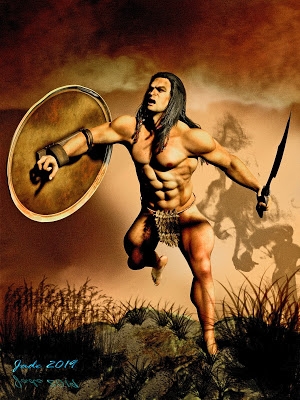

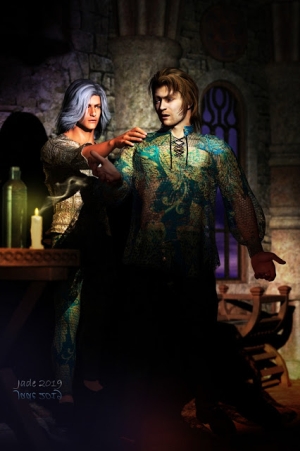

As promised -- the next part of Abraxas: The Lost Songs, before the month is out. And ... talk about "recycled artwork!" This was developed from one of the original panels that was rendered for the old graphic novel version of the story. The problem was, back in those days, I couldn't rayrace to save my life (all I got was a crash to the desktop), and everything had to be rendered small (same reason). So when I delved back into the art that was left dangling after the end of the uploaded part of the story -- right on the cusp before it was abandoned, due to being categorized as porn by some genius at Project Wonderful -- all I had to work with was a bunch of small, primitive renders. And, due to moving house, theres no time right now to wrangle anything new...

Hmmm. What could I do?

Well, I doubled the size of the art, and then doubled it again, but -- duh! -- it went soft in the resizing. Then, I started painting ... and what you see here is mostly painting, right over the old render. Hair, skin tones, trees, shrubs, shadows, highlights, chimney smoke, birds, sky, vines ... everything was added in, at the painting stage; and a lot more. Because the design of things has changed on a subtle level, between the old (January 2010) art, and the new.

If you look closely here, you're going to see what looks like "continuity errors." Uh huh. Best I could do was change the color of things to get them closer to "right."

The end of the process, thought, still left me with a soft, soft image, and I thought ... hmm. Suppose we treat this like a painting? So I added an extra layer: canvas paper. If you view the art at large size (1600 wide), you'll see that it's been processed to look like an oil painting on canvas paper. Neat. In fact, this covers the proverbial multitude of sins.

I'll be returning to this art, when there's time, and will be rendering something new, but this is actually a pretty cool stopgap.

And -- weehoo! -- the narrative has now passed the end of what appeared in the graphic novel version, and we're forging ahead into new material!

If anybody out there can see the porn in this tale, please point it out to me, because I'll be damned if I can see it.

House moving update: more of same. Boxes, packing, bubble wrap, tape, scissors, craft knives, schnoodles, burlap ... exhaustion. It's hot, and I really am starting to crash and burn. We get the keys in a day and a half and can actually start moving stuff. There's a looong way to go, but we're determined to be in by Christmas!

Jade, November 28